A lovely article by Nina Shapira appearing in the Seattle Times

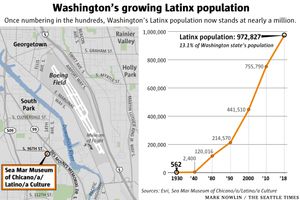

When Rogelio Riojas looks at 1950s farmworker cabins, transplanted from Eastern Washington to a new museum of Latinx history in Washington, things quickly get personal.

Two small shingled cabins — outfitted with furniture, dishes and other objects from the time — are not just history for Riojas, president and CEO of Sea Mar Community Health Centers. They’re a snapshot of his childhood.

Taking a break this week from preparations for Thursday’s opening, as workers around him drilled and painted, the 69-year-old Riojas recalled living in such cabins with his parents and 11 siblings. The big family would often occupy two of them. “You would find a place to sleep, sometimes a bed, sometimes on the floor,” he said.

Riojas has long had a dream to build a museum that would tell the story of families like his. He roped several other farmworkers’ children into the project, including architect José Bazan and historians Jerry Garcia and Erasmo Gamboa. And so was born the Sea Mar Museum of Chicano/a/Latino/a Culture, a mouthful of a name that avoids the simpler, gender-neutral term “Latinx” in favor of terms used in the periods portrayed.

The project in Seattle is the first of its kind, according to officials there and at other museums around the state. Free of charge to visitors, it fills two large rooms, 8,500 square feet in all, within a newly constructed building on the edge of South Park that also houses a Sea Mar adolescent health clinic, community center and Spanish-language radio station KKMO El Rey.

The telling of this history, through artifacts and photos, has a mission — to document the often-overlooked contributions of the Latinx population and counter the narrative describing immigrants and their offspring as a drain on society.

var mth = mth || []; mth.push({‘placement’:’rstag3017′});

</div><amp-analytics>{“transport”: {“beacon”: true, “xhrpost”: false},”requests”: {“ampeos”: “https://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pcs/activeview?xai=AKAOjssiesElFOPXsxpLLDySvRl2J6Gl-oe2AEMpO4Lfjl5T2J1JbiUhrG2PikR-G7dQLX3w_EQy5TqW3uR2Z2M6lFDJqa4F0c1o5rERvP_NI0o&sig=Cg0ArKJSzKLyYNlLFXNQEAE&id=ampeos&o=${elementX},${elementY}&d=${elementWidth},${elementHeight}&ss=${screenWidth},${screenHeight}&bs=${viewportWidth},${viewportHeight}&mcvt=${maxContinuousVisibleTime}&mtos=0,0,${maxContinuousVisibleTime},${maxContinuousVisibleTime},${maxContinuousVisibleTime}&tos=0,0,${totalVisibleTime},0,0&tfs=${firstSeenTime}&tls=${lastSeenTime}&g=${minVisiblePercentage}&h=${maxVisiblePercentage}&pt=${pageLoadTime}&tt=${totalTime}&rpt=${navTiming(navigationStart,loadEventStart)}&rst=${navTiming(navigationStart)}&r=de&isd=${initialScrollDepth}&msd=${maxScrollDepth}”},”triggers”: {“endOfSession”: {“on”: “visible”,”request”: “ampeos”,”visibilitySpec”: {“reportWhen”: “documentExit”,”selector”: “:root”,”visiblePercentageMin”: 50}}}}</amp-analytics>

// seattletimes

// Add this tagging to a DFP Professional creative wrapper and associate the corresponding label with all ad units on this site

(function(cid, mkt, config, domain) {

var _matherq;

var topWindow;

try {

window.top.document && (topWindow = window.top);

}

catch (e) {

topWindow = window;

if (!topWindow._mather) {

(function() {

var ml = document.createElement(‘script’);

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0] || document.head;

var cb;

try {

if (!(cb = topWindow.localStorage._matherVer)) {

throw false;

}

} catch (e) {

cb = Math.round(new Date() / 1.0368e9);

}

ml.type = ‘text/javascript’; ml.async = true; ml.defer = true; ml.id = ‘_mljs’;

ml.src = (‘https:’ == topWindow.location.protocol ? ‘https’ : ‘http’) + ‘://’ + (domain || ‘js.matheranalytics.com/s’) + ‘/’ + cid + ‘/’ + mkt + ‘/’ + (config ? config + ‘/’ : ”) + ‘ml.js?cb=’ + cb;

s.parentNode.insertBefore(ml, s);

topWindow._mather = {};

})();

}

}

_matherq = (topWindow._matherq = topWindow._matherq || []);

_matherq.push([‘trackUnstructEvent’, ‘Ad Impression’, { eaid: ‘4382891005’, ebuy: ‘549100399’, eadv: ‘146230399’, ecid: ‘138208122355’, eenv: ‘i’, epid: ‘83203399’, esid: ‘80279479’ }]);

})(‘ma39482′,’93382992’,”);

{"uid":0.43743760121863595,"hostPeerName":"https://www.seattletimes.com","initialGeometry":"{\"windowCoords_t\":0,\"windowCoords_r\":1280,\"windowCoords_b\":634,\"windowCoords_l\":0,\"frameCoords_t\":5187,\"frameCoords_r\":790,\"frameCoords_b\":5437,\"frameCoords_l\":490,\"posCoords_t\":3077,\"posCoords_b\":3327,\"posCoords_r\":790,\"posCoords_l\":490,\"styleZIndex\":\"\",\"allowedExpansion_r\":980,\"allowedExpansion_b\":384,\"allowedExpansion_t\":0,\"allowedExpansion_l\":0,\"yInView\":0,\"xInView\":1}","permissions":"{\"expandByOverlay\":true,\"expandByPush\":true,\"readCookie\":false,\"writeCookie\":false}","metadata":"{\"shared\":{\"sf_ver\":\"1-0-36\",\"ck_on\":1,\"flash_ver\":\"26.0.0\",\"canonical_url\":\"https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/first-museum-of-latinx-history-in-washington-opening-in-seattle-tells-overlooked-story/\",\"amp\":{\"canonical_url\":\"https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/first-museum-of-latinx-history-in-washington-opening-in-seattle-tells-overlooked-story/\"}}}","reportCreativeGeometry":false,"isDifferentSourceWindow":false,"sentinel":"0-2900920124561150309","width":300,"height":250,"_context":{"ampcontextVersion":"1911062056110","ampcontextFilepath":"https://3p.ampproject.net/1911062056110/ampcontext-v0.js","sourceUrl":"https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/first-museum-of-latinx-history-in-washington-opening-in-seattle-tells-overlooked-story/?amp=1&__twitter_impression=true&fbclid=IwAR1lAKlcP1nS_wjmS0tgd-BnxOS_XtPPFCvEm2fJHL4TFBJZb8vkLkNZ8Ig","referrer":"https://www.facebook.com/","canonicalUrl":"https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/first-museum-of-latinx-history-in-washington-opening-in-seattle-tells-overlooked-story/","pageViewId":"1228","location":{"href":"https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/first-museum-of-latinx-history-in-washington-opening-in-seattle-tells-overlooked-story/?amp=1&__twitter_impression=true&fbclid=IwAR1lAKlcP1nS_wjmS0tgd-BnxOS_XtPPFCvEm2fJHL4TFBJZb8vkLkNZ8Ig"},"startTime":1573405993335,"tagName":"AMP-AD","mode":{"localDev":false,"development":false,"minified":true,"lite":false,"test":false,"version":"1911062056110","rtvVersion":"011911062056110"},"canary":false,"hidden":false,"initialLayoutRect":{"left":0,"top":3077,"width":1280,"height":250},"initialIntersection":{"time":3293,"rootBounds":{"left":0,"top":0,"width":1280,"height":634,"bottom":634,"right":1280,"x":0,"y":0},"boundingClientRect":{"left":0,"top":967,"width":1280,"height":250,"bottom":1217,"right":1280,"x":0,"y":967},"intersectionRect":{"left":0,"top":0,"width":0,"height":0,"bottom":0,"right":0,"x":0,"y":0},"intersectionRatio":0},"domFingerprint":"486346303","experimentToggles":{"pump-early-frame":true,"chunked-amp":true,"amp-ad-ff-adx-ady":false,"amp-consent-v2":true,"canary":false,"amp-story-v1":true,"hidden-mutation-observer":true,"fix-inconsistent-responsive-height-selection":false,"a4aProfilingRate":false,"version-locking":true,"amp-auto-ads-adsense-holdout":false,"as-use-attr-for-format":false,"adsense-ad-size-optimization":false,"blurry-placeholder":true,"amp-playbuzz":true,"flexAdSlots":false,"amp-action-macro":true,"fixed-elements-in-lightbox":true,"amp-access-iframe":true,"ios-scrollable-iframe":false,"doubleclickSraExp":false,"amp-sidebar-swipe-to-dismiss":true,"doubleclickSraReportExcludedBlock":false,"ampdoc-closest":true,"amp-story-responsive-units":true,"ios-fixed-no-transfer":false,"macro-after-long-task":false,"use-responsive-ads-for-responsive-sizing-in-auto-ads":false},"sentinel":"0-2900920124561150309"}}” width=”300″ height=”250″ frameborder=”0″ marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” sandbox=”allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox allow-forms allow-modals allow-pointer-lock allow-popups allow-same-origin allow-scripts” allowfullscreen=”allowfullscreen” data-amp-3p-sentinel=”0-2900920124561150309″ data-mce-fragment=”1″>

“We came here to work,” Riojas said. “Over the years, we have been a big part of the success of the agricultural industry in this state.”

The museum aims to tell another story, too, he said, of farmworkers’ children who got an education and became professionals and social-justice activists. It highlights the role of the University of Washington, which in the 1960s started an affirmative-action program that sent recruiters to Eastern Washington towns like Othello, where one of them found a teenage Riojas.

Mexican Americans are the focus, at least for now. Garcia, who worked at Northern Arizona and Eastern Washington universities before joining Sea Mar as vice president of the museum and other programs, said that’s because Washington didn’t get a critical mass of other Latin American immigrants until civil wars sent them fleeing here in the ’80s.

Latinx artists forging their future in the artworld

Please take a look at this wonderful article by Maria Trujillo for Art Critique

Latinx artists and advocates are pushing the boundaries of language and gender in the art world. By relinquishing the gendered terms of latina or latino, creatives are exploring their art practice with renewed freedom. Adding Latinx to their lexicon of identifiers, more and more museums and galleries are applying the term to artists of Latin American descent. Latinx artists are gaining traction likely because of the wave of social justice activism around the globe and the poignant themes tackled in their work: immigration, debt, and sexual identity.

The term of Latinx formed roots in 2004 through the LGBTQ community but gained popularity across social media in 2016. Although many cultural institutions are including the word as part of their best practices, who the term actually includes remains ambiguous. Dictionaries define the word as: “relating to people of Latin American origin or descent (used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina).” This identifier thus departs from the patriarchy inherent to the Spanish language, where a mixed group of gendered people takes on the masculine identifier – in this case, Latinos.

The definition of Latinx is inclusive, but because the term has strong sociocultural connotations and is politicized in the art world, some artists and curators to whom Latinx applies are hesitant to use it. Some people question whether they are enough of an activist or sufficiently Latino or Latina – either because only one of their parents emigrated from Latin America or because they are part of the second or third generation to be born in the United States. An associate curator with whom I spoke last year felt hesitant to use the term to describe herself despite her willingness to adopt it. She needed to identify herself for an upcoming symposium on Latinx artist but was concerned that, because her parents came from Brazil, she may not be able to use Latinx.

Latin American artists living in the United States and those who choose to identify as Latinx already face significant barriers from art museums. Analyzing over 40,000 artworks in the collections of 18 museums across the US, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts, to determine the gender and ethnic diversity of their collections, a recent survey by the Public Library of Sciences (PLOS)found that 85% of artists represented in these collections are white and 87% are men. This data does not represent the makeup of the United States; the last census concluded 18% of the US population to be of Latin American origin and 50.8% of the total population to be female.

Several Latinx artists use the artworld’s gender and ethnic inequity in their work. Barbara Calderón is an artist, writer, activist, and founding member of the art collective Colectiva Cósmica. With a dynamic background in journalism, art history, and Xicana studies, she aims to increase awareness of Latinx’s importance while also exploring the complexity of gender in her practice. In an interview with the New York Times, she elaborated on the driving force behind her work: “History is always kept from us,” Barbara Calderón said. “When we start learning about our histories, and we start gaining pride in our personal history, we want to incorporate that.”

While the landscape of cultural institutions continues to evolve, an awareness of the lack of diversity and efforts to overcome shortcomings is a leap in the right direction. The Latinx, Chicanx, and other such movements challenge us to question the inflexibility of language and molds. To learn more about the Latinx art community or find different ways to get involved, you can visit the US Latinx Art Forum.

Exhibit on US Latina ‘cholas’ opens in Albuquerque

Check out this article on a new exhibit in Albuquerque written by Russell Contreras for the Sentinel: https://cumberlink.com/travel/exhibit-on-us-latina-cholas-opens-in-albuquerque/article_c0b70512-0c5a-51b2-b56d-ac66744817f4.html?fbclid=IwAR3X9zS-DOmWQNmVcpLkK0c7ThgNIDHb0WjnBDCJ-aE-OMVdq7E6RE1eH6w

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — A national Hispanic center is displaying a unique art exhibit on the chola — the working class, Mexican-American urban female often associated with gangs.

The National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque opened the “Que Chola Exhibition” on Friday with pieces by artists from New Mexico, Arizona, California, Texas, and Colorado.

The displays feature the evolution of the chola from the World War II-era to the contemporary figure trying to survive in poor neighborhoods. Using paintings, photography and sculptures, the exhibit attempts to cover images of the chola as an urban warrior, a mentor, a mother and political figure.

Cholas, or homegirls, often refers to a particular Latina subculture in the U.S. characterized by a tough demeanor and distinctive style. They are identified by their clothing ranging from flannel shirts and khaki pants to their dark eye makeup and indigenous-theme tattoos.

The image of the chola gained popularity in the late 1980s and early 1990s with movies like “Colors” and “Mi Vida Loca” (My Crazy Life).

In recent years, scholars have countered that the chola represents more than just gang activity. Latina scholars have argued that the chola’s image is a commentary of poverty in urban U.S. cities and symbolized a working-class Latina seeking to battle sexism.

Some Latina academics have playfully said on social media that “you can’t spell scholar without the word ‘CHOLA’.”

Curator Jadira Gurule said she agreed that the chola is more than a so-called dangerous female gang member linked to criminal activity. For many Latinas, Gurule said the chola also represents strength and perseverance.

“Many within our communities either were, or admired and wanted to emulate, the chola growing up,” Gurule said. “She also represents real people with real experiences. The chola is a persona developed in response to racism and sexism. To reduce her to a gang member is shallow.”

Pola Lopez, a Las Vegas, New Mexico, born artist who now lives in Los Angeles, said she was excited when she was asked to participate in the exhibit. “The chola…you can’t mess with her,” said Lopez. “She’s beautiful and represents us in many ways.”

Her painting, “Coatlicue and Chola,” features a homegirl leaning against a statue of an Aztec goddess.

Nanibah Chacon, a Navajo and Hispanic artist from Arizona, said she wanted to create an image of a chola if she had been represented in midcentury advertisements. Her painting, “Xicana Classic,” depicts a chola from the 1970s sitting on a red circle and smiling with confidence.

The exhibit, which runs until Aug. 4, is the latest attempt to create a new image around the chola and expand her meaning.

The Los Angeles-based gang intervention group Homeboy Industries, for example, sells clothing designed by former cholas and runs Homegirl Cafe — a restaurant with food prepared by former gang members gaining new skills. The hip cafe is an offshoot of social enterprises founded by Jesuit priest Greg Boyle.

And Art Laboe, a 93-year-old DJ based in Palm Springs, California, allows cholas every Sunday on his syndicated oldies show “The Art Laboe Connection Show” to call in and give dedications to their loved ones serving time in prison. Scholars and activists say the radio show helps humanize cholas since it allows listeners to hear cholas express emotions of love and pain.

———

Associated Press Writer Russell Contreras is a member of The Associated Press’ race and ethnicity team. Follow Contreras on Twitter at http://twitter.com/russcontreras

———

This story corrects a previous version with the quote “you can’t spell scholar without the word ‘CHOLA’.”

BORDER STORIES TOLD THROUGH COMIC ART

Jasmin Medrano gives a dynamite write up of the comic El Peso Hero to promote its exhibit at Texas A&M University: http://maroonweekly.com/border-stories-told-through-comic-art/?fbclid=IwAR1NBjBZNGnevMC3f7OzsENR8SydtCKf8_3cr6v-ELdR3Hd6BoFAYx7E4uc

With all of the negative drama at the border spiraling, one artist turns the tables, making it a positive platform for a public servant vigilante. The MSC Visual Arts Committee is proud to present artwork by comic artist Hector Rodriguez that will feature a Latino comic book superhero series known as “El Peso Hero” who shows the struggles of both sides.

Based on a rogue hero battling border issues such as Mexican cartels, human trafficking, and border corruption, the popular series has gained wide international media attention, including coverage by CNN, UNIVISION, and TELEMUNDO. And even though his comics are captioned in Spanish, his audience remains large and open to all.

Rodriguez himself is not superhuman but a bilingual educator who works with low-income students who come from the same unfortunate background as the refugees in his comics. The hero is said to defend Mexican refugees that cross the border to evade violence and government corruption, and is highly skilled in hand-to-hand combat with strength and immunity just like Superman. The cartoon style makes it more accessible to kids. Not only is the hero relatable, but the series also shares the border struggles in a different light. Latinos are not typically featured in comic books, much less featured on the covers, and it became a goal of Rodriguez’s to give his students a role model.

While the comics do not take a political stance, Rodriguez does try to counter the negative rhetoric he feels is incited by 45th president of the United States, Donald Trump. Rodriguez even created a special Donald Trump cover that shows the main protagonist, “El Peso Hero” knocking his fist into President Trump’s face.

With the comic series being a unique and tasteful blend of history, art, and current events, it is a powerful demonstration of art with a message. The showcasing will take place Wednesday, January 16, 2019, at 9:00 a.m. through Sunday, March 3, 2019, at 8:00 p.m. in the MSC Reynolds Gallery.

Latino Art Now! in Houston on April 4-6th!

On April 4-6, 2019, the Latino Art Now! Conference: Sight Lines & Time Frames will take place at the University of Houston Student Center South. LAN! will explore and celebrate the activities and practices of local and national Latino and Latin American visual artists and organizations throughout Houston.

Now in its 6th edition, the Latino Art Now! Conference is recognized as the leading forum for visual artists, art historians, curators, collectors, and educators.

Mari Carmen Ramírez, Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, will deliver the keynote address.

Latino Art Now! is organized by the Inter-University Program for Latino Research (IUPLR) headquartered at the Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of Houston and is sponsored by the Office of the Provost.

Additional sponsors include: Southwest Airlines, the City of Houston, Houston Endowment, University of Houston, Smithsonian Latino Center, University of Houston-Downtown, Houston Arts Alliance, Houston First, Visit Houston, ClearChannel Outdoor, and Allegiance Bank.

Lowriders, Aliens and Cultural Hybridity in the Work of Rubén Ortiz-Torres

This fall and winter, the Getty’s ambitious Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative sprawls across dozens of Southern California institutions, presenting a broad range of exhibitions on Latin American and Latino Art in Los Angeles. It is widely considered to be a watershed cultural moment, highlighting often-overlooked artists and movements who are being finally given institutional due. Six years ago, however, a single exhibition included in the inaugural LA-focused Pacific Standard Time explored many of the same themes that are now being considered on a much larger scale. “MEX/LA: “Mexican” Modernism(s) in Los Angeles, 1930-1985” at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach could be considered a precursor to PST:LA/LA, tracing the legacy of Mexican artists like David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco in LA through the Chicano Art Movement of the 60s, and beyond.

“MEX/LA…is a show that pretends to tell an L.A. history or a Mexican history that has not often been told as either, and yet it is both and it is important,” exhibition curator and artist Rubén Ortiz-Torres writes in his catalogue essay, “Does L.A. stand for Los Angeles or Latin America?,” a question that could just as easily apply to the current PST:LA/LA series. “Like any other history it is partially true and forgets something else. It is a fragmented and contradictory one with different points of view that often clash and differ but are necessary pieces of an incomplete puzzle…It is a show about conflict, misinterpretation, appropriation, fascination, resilience, and more.”

Just as the show he curated can be seen as harboring the seeds of the larger PST:LA/LA project, through his own work over the past three decades in sculpture, video, installation, photography, and more, Ortiz-Torres has grappled with and celebrated themes of hybridity, identity and cultural transmission that weave through many of the exhibitions now on view.

“He’s an important voice at the intersection, not only of transplanetary, but transnational borders,” says Robert Hernandez, who included Ortiz-Torres’ work in “Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas,” an exhibition he co-curated at UC Riverside. “He was at the forefront of that kind of hemispheric dialogue, not just bi-national between Mexico and the US, but in relation to Americas in the whole.”

Born in Mexico City in 1964, he moved to Southern California in about 1990, and this dual identity as a Mexican, but also as a Mexican-American, is a focal point in his work. (Even before moving North, he had an affinity for the US national pastime as he notes in his bio: “After giving up the dream of playing baseball in the major leagues he decided to study art,” and he can often be seen wearing a Dodgers jersey and ubiquitous L.A.-baseball hat).

As a young artist in the 80s, Ortiz-Torres was never content to stick with one style, his work changing so rapidly that curators were often left befuddled.

“My work has always been very eclectic,” he notes. “They would come to my studio and say, ‘Let’s do a show but let’s see how your work evolves.’ So we had a meeting six months after that, and they said, “But the work is different, we like the old work.’ It’s like, ‘Well now I’m doing this.’”

Ortiz-Torres was a peer of several of the artists who would go on to international recognition in the 90s like Gabriel Orozco, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Carlos Amorales, and Gabriel Kuri (he was actually high school classmates with Orozco), however, he left for LA just as Mexico’s contemporary art scene was exploding.

“Through an accident of destiny I met the filmmaker Catherine Hardwicke [director of “Twilight”],” he recalls. “She says, ‘come to Los Angeles, go to CalArts.’”

After applying, Ortiz-Torres was accepted to CalArts but lacked the funds to pay for tuition, which he solved by landing a grant to cover expenses.

“Once I got the grant they said, ‘You can go to New York or Chicago or wherever,’ but for me, it was like a reality check. The things I was dealing with in Mexico City would make sense in LA somehow,” he says. “Also if everything goes bad I can go to Tijuana in a couple of hours.”

The things he was dealing with were directly related to the hybridity, mutability and messiness of culture, of how to convey the breadth of the Mexican experience without essentializing it.

“What I saw as this big conflict for Mexican culture at large was how can you be modern and contemporary and yet negotiate with local and specific cultural traditions?” he says. “In the history of Mexican Art, what you really see is this schizophrenic pendulum of conflict. You either have nationalism, like Rivera, the Mexican School, where you have to look at our indigenous cultures, and resist European cultural colonialism, or the rejection of that nationalism, which says we’re part of the rest of the world, we’re part of the international community.”

In Los Angeles, he found an ideal expression of this creative conflict in the quintessentially SoCal phenomenon of the customized Lowrider car show.

“The car show is obviously modernistic, but at the same time, it has all this other stuff. At CalArts, they kept talking about multiculturalism, as this theoretical thing, and about interdisciplinarity, and I thought, ‘What the hell are these things? Are they sculptures, are they performances? The painting is fantastic.’” He recalls. “It was dangerous. You would go to the car shows and there would be shootings. One kid got stabbed with a trophy.”

Fittingly, the car shows in L.A. were not Ortiz-Torres’ first experience with Lowrider culture. As a child, he had gone to Michoacan with his grandfather to celebrate Christmas, and it was there that he saw his first Lowrider, a Southern California export presumably driven down by a Mexican-American to Mexico.

He began making works based on Lowrider customization, the most well-known of which is “Alien Toy” (1997), a border patrol truck that breaks apart and mutates into a dancing robot. As with many of his car creations, this was a collaboration with Salvador Muñoz, a self-taught Lowrider artist who regularly competes in car shows. “He’s originally from Jalisco, so he has kind of an outsider interpretation of Lowriders, which is itself an interpretation of hot rod car culture, which is already an outsider interpretation of cars,” Ortiz-Torres notes.

Alien Toy is currently on view in “Mundos Alternos,” dancing for the first time in many years at the opening. “Rubén’s work has historically been rife with humor and parody,” says Hernandez, the show’s co-curator. “One way he comments on our social reality is through the guise of the alien. Himself, a resident alien, riffing on that in a number of ways, juxtaposing literal green men with INS raids.”

In addition to the inclusion of his own work in PST:LA/LA, Ortiz-Torres also co-curated “How to Read El Pato Pascual: Disney’s Latin America and Latin America’s Disney” on view at the MAK Center and the Luckman Fine Arts Complex. Taking its title from “How to Read Donald Duck,” a 1971 Chilean book that applies a Marxist critique to Disney’s exportation of American culture, the two-venue exhibition features artists throughout the Americas who reflect this critique with irony and humor. Several works meld familiar images of Disney characters like Mickey Mouse with figures of Aztec or Mayan deities. For Ortiz-Torres, this relationship has a special significance here in California, Disney’s home. “The conflict that we pay a lot of attention to is between pre-Columbian culture, indigenisms, and modernisms, which in California has always existed. The Annenbergs and other collectors in California collected both at the same time.”

Ortiz-Torres’ most recent work is on view in “White Washed America,” at Royale Projects in downtown L.A. Featuring glistening, abstract paintings made with urethane and metallic paints, the show brings together several themes that he has explored over the years: car culture, punk rock, minimalism and American identity — in both the national and hemispheric sense. “Black Flag” (2014), comprised of four shiny, black rectangular panels — two hung and two leaning against the wall — succinctly captures it all, referencing both the L.A. punk band’s iconic logo designed by Raymond Pettibon, as well as the “Finish Fetish” school of mid-century California minimalism. “El Grito (The Scream)” (2014) is part painting, part performance, a radiant orange work that changes color once the viewer screams at it. Incorporating thermochromatic paint and unseen electronics, it is a technological mutation of El Grito, the Mexican cry of Independence.

“Plata o Plomo (Silver or Lead)” (2017), is an expressionistic, metallic composition inspired by drug kingpin Pablo Escobar’s phrase outlining the two ways to accomplish your goals: “Plata o Plomo,” bullets or bribery. The work takes on a grim significance considering the U.S.’s current situation of overwhelming violence and corruption.

One of the only representational works in the show, “White Washed America” (2014) recreates “América Tropical,” a 1932 mural by famed Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros commissioned for Olvera Street in downtown LA. Depicting a crucified indigenous peasant, the controversial work was whitewashed shortly after completion, only recently being uncovered and restored. Ortiz-Torres’ version is rendered in chromaluscent pearl paint, a glowing, ghostly image that one must struggle to ascertain. He excavates this important artifact, only to obscure it again beneath additional cultural and artistic layers. In many ways, Ortiz-Torres is not interested in answering the question, “What is Latin American or Latino Art?”, but in further complicating the conversation.

“It seems that for us in America, we don’t really know how to locate ourselves, especially when it comes to constructing identity,” he explains. “This is something that unifies the whole continent. Even Jackson Pollock, where is he gonna draw from, Native American sand paintings or the history of Western art? He doesn’t know. It’s a real cultural dilemma. For Frank Lloyd Wright too. ‘Do I refer to the Greeks or the Mayans? At some point, he realizes they are both are valid, that the Greeks are not necessarily the default. They might be as alien to him as the Mayans.”

Top Image: Rubén Ortiz-Torres. La jaula de oro (Gilded Cage), 2017 | Courtesy of Royale Projects.

‘Bridges in a Time of Walls’ Brings Chicano Art to Mexico City

See original post by Samanta Helou Hernandez for KCET here: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/bridges-in-a-time-of-walls-brings-chicano-art-to-mexico-city?fbclid=IwAR05lKkfmbROId8O7d3pXwi1Z-jPXHKsinODZLUcT6X6DAQm7zbi8-qwCcQ

“Es arte Chicano,” explains a mother to her young daughter, “de gente Mexicana que vive en Estados Unidos.” (“It’s Chicano art, from Mexican people who live in the United States.”) The little girl has an awestruck expression as she walks up the winding path of Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil. The pair stops to observe mural-sized paintings, sculptures and colorful installations, all made by Mexican-American and Chicano artists from Southern California.

“Bridges in a Time of Walls: Mexican/Chicano Art from Los Angeles to Mexico” is a wide-ranging, multigenerational and rare exhibit of Chicano artwork in Mexico’s capital on view until November 25, 2018. The exhibit, organized thematically rather than chronically, with work from artists like Patssi Valdez, Carlos Almaraz and Patrick Martinez, among many others, seeks to complicate the narrative and challenge misconceptions of what Chicano art is while contributing to a much-needed dialogue between Mexico City and Southern California.

“You have a group of people who are born with Mexican heritage who have chosen to explore themes to help them and others understand that they are more than just Mexican and more than just American,” explains Julian Bermudez, the exhibition curator.

Despite the violent rhetoric around immigration in the United States, 36.3 million people in this country identify as being full or of partial Mexican ancestry. It’s hard to find a person in Mexico who doesn’t have a relative or friend that immigrated to the United States. This makes understanding the conditions of Mexican-Americans and Chicanos that much more critical; and art is a poignant vehicle to do so.

“Mexico City is a significant art center, and there’s a significant exchange with New York. The same doesn’t necessarily happen with Chicano art,” explains Chon Noriega, a professor of Chicano studies at UCLA, curator, and contributor to the exhibition’s catalog. “It’s an important dialogue to have between Mexico City and Los Angeles.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT CHICANO CULTURE

-

Lowriders, Aliens and Cultural Hybridity in the Work of Rubén Ortiz-Torres

“Bridges in Times of Walls” is a collaboration between the Mexican government’s cultural department and AltaMed Health Services — the United States’ largest federally-qualified health center, which also boasts an extensive collection of over a thousand pieces of art, many of which are by Chicano artists. The idea of inaugurating a Chicano art show in Mexico City came about after the overwhelmingly positive reception of “Before the 45th: Action/Reaction in Chicano and Latino Art,” an exhibit at the Mexican Cultural Institute in Washington D.C. by AltaMed.

Walking up the ramps of the museum, visitors are greeted with a bilingual text introduction detailing the experiences of Chicanos in the United States and the art created in response. Eighty-eight pieces of art take up the third floor. The glow of a liquor store-like neon sign with the phrase “Brown Owned” by Los Angeles artist Patrick Martinez fills the right side of the room, its words cleverly celebrating everyday imagery we take for granted. Photographs of performance art by the avant-garde 1970s collective Asco follows soon after. Proceeding in a circular fashion, the exhibition is thematically divided into five sections: Rebel Diamonds from the Sun, Imagining Paradise, Outsiders in their Own Home, Mapping Identity and Cruising the Hyphenate.

“Rebel Diamonds in the Sun” serves as an introductory section to the inception of Chicano art as a visual response to the social movements of the 1960s and 70s. The conceptual work of Asco is placed alongside the overtly political paintings of 70s Chicano art collective, Los Four. By showing a diverse set of visual and conceptual styles made from the 1970s to today, the exhibit contradicts false ideas around Chicano art as limited to one set of forms or subjects. “An exhibition like this gives an opportunity for an audience in Mexico to see a much more expanded array of art,” says Pilar Tompkins Rivas, the curator of Vincent Price Museum and an advisor on the project.

In “Imagining Paradise,” we see the way artists across generations respond to their built environment in vastly different ways. The explosive brush strokes and vibrant colors in Carlos Almaraz’s depiction of Echo Park finds itself next to Shizu Saldamando’s representational painting of a Highland Park kickback created on Japanese multi-panel rather than canvas. Saldamando celebrates everyday life in the historically Latino neighborhood while using elements that represent her own identity as a biracial woman of Mexican and Japanese descent.

In the middle of it all is Ana Serrano’s “Cartonlandia,” a mountainous cardboard structure of colorful homes inspired by neighborhoods in Mexico. Serrano’s work conveys the ways in which Latino barrios often resist Eurocentric aesthetic standards of visually-unified neighborhoods through a liberal use of color and texture. The multicolored neighborhood could easily be found in Mexico City, Tijuana or South Central.

Contemporary artist Ramiro Gomez places domestic workers on the pages of luxury home magazine in “Outsiders in their Own Home” conveying the experience of being ni de aqui ni de alla, (neither from here nor there,) of not being fully embraced by Americans or Mexicans. By re-imagining photographs of perfectly manicured backyards and clean homes, we are confronted with the often forgotten labor behind these realities.

Performance artist Gabriela Ruiz, also known as Leather Papi, created a monochromatic room of re-imagined furniture found during her excursions of through Mexico City’s streets. By giving these disposed objects new life, Ruiz questions her own relationship to the idea of home in “Mapping Identity.” Artists in this section created work that explored questions around belonging, sexuality, gender and immigration.

“Today it really is more about one’s own perception of self,” explains Tompkins Rivas. Artists in this section looked inward to create work that explores questions around belonging, sexuality, gender and immigration. “Historically there’s been a tendency and need to make the term [Chicano Art] mean one thing or a movement of specific images that came out of maybe only muralism or printmaking. While those are important, art production is so much more complex than that,” explains Tompkins Rivas.

As the circle comes to an end, “Cruising the Hyphenate” uses the metaphor of a car to show the in-betweeness of Chicano identity while celebrating an object (the car) that has a vast cultural relevance for Chicanos in Los Angeles. That the exhibition physically comes full circle is a reflection of its non-linear curation but also of the non-linear nature and evolution of Chicano cultural production.

Through various conversations with Mexicans in Mexico City viewing the artwork, it was apparent that stereotypes are still persistent. Many mentioned films like “Blood in Blood Out” as their introduction to the idea of a Chicano, while others described the art of cholos as their only exposure to Chicano art. Yet, all were pleasantly surprised to see the scope of artistic production by Chicanos ranging from sculpture, surrealism, realism, performance, video, conceptual art and beyond. “What impresses me is the great diversity of the exhibit and an array of artwork that still preserves a Mexican essence,” describes one attendee in Spanish.

Whether it’s through questioning alienation, migration, environment, politics, sexuality or gender, each artist, across different time periods engages with their identity in myriad ways. Ultimately, it exposes Mexicans in Mexico to sides of the Chicano and Mexican-American experience that they otherwise might not have seen. Throughout the opening weekend, curators and art workers from both sides of the border reiterated the importance of understanding the shared experiences between Chicanos and Mexicans, especially during a time where the livelihoods of Mexicans in the United States are in constant threat. They stressed in Spanish and English that, “la cultura no tiene fronteras,” (“culture has no borders.”)

New Exhibit: Califas: Art of the US-Mexico Borderlands

Anyone near the Richmond Art Center between now and November 16th? This looks like it’s worth checking out.

http://richmondartcenter.org/exhibitions/califas-art-of-the-us-mexico-borderlands/

Califas: Art of the US-Mexico Borderlands / El Arte de la Zona Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos explores representations of the US-Mexico ‘borderlands’ in contemporary art, with a special emphasis on the Bay Area.

This exhibition comes at a moment when the current nationwide immigration crisis has once again focused attention on the border between Mexico and the United States. Californian communities, activists, politicians, and artists have been especially vocal in this crisis.

Featuring works by 21 contemporary artists and collaborative groups, Califas explores the origins of migrant memory, the consequences of boundary line fortifications, the mixing of border cultures, responses to injustice and inequality, and solutions to advance the borderlands and its peoples.

The exhibition adopts a unique lens to re-examine the past, grapple with understanding the present, and connect with the future of a distinct cross-border culture. The name Califas is commonly used to refer to California by Chicanos wishing to emphasize the deep histories, memories, and identities that existed in the state long before the international boundary was created in 1848. Adapted for use in this exhibition, Califasprovides new ways of seeing California and Baja California – as borderlands before walls, when people understood the border as a connecting tissue not a line of separation.

Featured Artists: AGENCY (Ersela Kripa & Stephen Mueller), Chester Arnold, Jesus Barraza, Enrique Chagoya, CRO studio (Adriana Cuellar & Marcel Sánchez), Ana Teresa Fernández, Nathan Friedman, Guillermo Galindo, Rebeca García-González, Andrea Carrillo Iglesias, Amalia Mesa-Bains, Richard Misrach, Alejandro Luperca Morales, Julio César Morales, Postcommodity, Rael San Fratello (Ronald Rael & Virginia San Fratello), Fernando Reyes, Favianna Rodriguez, Stephanie Syjuco, David Taylor, Judi Werthein, Rio Yañez

Califas is guest co-curated by UC Berkeley professors Michael Dear, author of Why Walls Won’t Work, and Ronald Rael, author of Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary.

The exhibition is made possible with support from the Zellerbach Family Foundation, Susan Chamberlin, Matt and Margaret Jacobson, and anonymous donors.

Image: Julio César Morales, Day Dreaming Series (detail), 2018. Courtesy of the Artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco

Latinos Remain Largely Excluded By Smithsonian Institutions, New Report Finds

original article by Mikaela Lefrak can be found here: https://wamu.org/story/18/09/10/latinos-remain-largely-excluded-smithsonian-institutions-new-report-finds/

The Smithsonian Institution has failed to achieve most of the goals it set for itself nearly a quarter of a century ago to improve Latino representation in its workforce, leadership and programming, according to an outside progress report released Monday.

The report, titled “Invisible No More,” details the ways in which the Smithsonian has overlooked Latinos in its executive ranks and budget priorities. It was released by UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center and the Latino Policy and Politics Initiative.

“There’s been a consistent pattern of Latino exclusion,” said Chon Noriega, a co-author of the study and the director of the Chicano Studies Research Center.

In “Invisible No More,” Noriega and his co-authors evaluate the Smithsonian’s progress on 10 goals the institution set in 1994 in a report called “Willful Neglect.” “The Smithsonian…displays a pattern of willful neglect toward the estimated 25 million Latinos in the United States,” wrote the authors in 1994. “It is difficult for the Task Force to understand how such a consistent pattern of Latino exclusion from the work of the Smithsonian could have occured by chance.”

The report included 10 recommendations for improvement, included supporting the development of a Latino Museum on the National Mall and increasing Latino representation across the Smithsonian’s workforce.

The findings of the new report from UCLA aren’t all bad. Two of the most promising growth areas are the curatorial and archival departments, which have added significant numbers of Latino specialists. In 1994, there were only two Latino curators. The Smithsonian established the Latino Curatorial Initiative in 2010, and between 2012 and 2016 there have been an average of 7 Latino curators per years.

However, the proportion of Latinos working at the Smithsonian still lags behind that of the total Latino population in the U.S.: Latinos made up 17.8 percent of the country’s population in 2017, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 1994, 2.7 percent of the Smithsonian’s workforce was Latino. In 2018, it’s only at 5 percent, according to the Smithsonian.

In terms of executive leadership, Latinos remain severely underrepresented. No Latinos served on the Smithsonian’s main governing body, the Board of Regents, before 1994, and only four have served since. There has been no Latino representation since 2016.

“When you look at leadership, the Smithsonian is on par with other major cultural institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Getty and the Chicago Art Institute, which have almost no minority leadership or governance,” said Noriega. “This is something that’s endemic to the field at large and really needs to be tackled.”

According to the Smithsonian, 3% of senior level leadership is Latino. A spokesperson said they are in the process of reviewing the report and its findings.

The report shows progress in other key areas, including Latino-centered collections, exhibitions and scholarship. The Smithsonian notes that the National Portrait Gallery has increased its acquisition of Latino subjects and artists by 90 percent, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture has recently begun to collect object related to the Afro-Latino experience.

However, the study’s authors point out that progress in these areas could be at risk due to inadequate federal funding for Latino-focused initiatives. The Smithsonian counters that it doubled its funding for Latino-related positions and programs in 2015 from $1 million to $2 million per year.

The Smithsonian has also failed in its goal to support efforts to establish a National American Latino Museum on the National Mall, according to the report. While private groups and Congressional leaders have repeatedly pushed for its creation, the authors say they could not find any mention of a Latino museum in any of the Smithsonian Institution’s annual reports from the last 23 years.

“Latinos remain largely excluded from participation in arts and cultural institutions that tell the American story,” Noriega wrote in the report’s foreword. “The Smithsonian has an opportunity to play a leadership role for the field.”

One of L.A.’s Most Iconic Chicano Murals Is Being Displayed in a Museum for the First Time Ever

For the original post by Gwynedd Stuart on LA Mag, click here: http://www.lamag.com/culturefiles/la-history-a-mexican-perspective/

On first glance, Chicana artist Barbara Carrasco’s 1981 mural L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective doesn’t look like the stuff of controversy. Originally commissioned for the city’s bicentennial, the mural consists of vignettes representing iconic events, people, and places in Los Angeles’ history, all tangled between the strands of a bronze-skinned woman’s flowing hair. The Hollywood sign jumps out at viewers, as do a bunch of oranges and the arched entryway to the Santa Monica pier. But upon closer inspection, it’s an unflinching look at events that shaped the city—both positive and negative.

As Daniel Hernandez wrote for LA Weekly, “The mural pays homage to slain L.A. journalist Ruben Salazar; playwright Luis Valdez and actor Edward James Olmos; to Biddy Mason, the last freed slave in Los Angeles, who founded the city’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church; and lesser-known figures, like Juan Francisco Reyes…the Spanish colonial town’s first elected alcalde—L.A.’s first-ever mayor chosen by the people was black and Spanish-speaking.

“Carrasco also painted Sandy Koufax alongside Dodger Stadium, reminding viewers of the violent displacement of Mexican-American families that took place in order to build the facility at Chavez Ravine. Hank Leyvas, one of the youth wrongfully accused in the 1942 Sleepy Lagoon trial, also is represented.”

When Carrasco refused to censor the mural’s content to make it a more friendly celebration of civic pride, the project was called off by the city, and Carrasco has since stored the mural in Pasadena at her own expense.

It was briefly displayed at Union Station late last year as part of LA Plaza and the California Historical Society‘s exhibit ¡Murales Rebeldes! L.A. Chicana/o Murals under Siege, although there were several instances when the mural was shrouded under black cloth at the request of individuals who’d booked private events at the depot.

From March 8, 2018, through April 21, 2019, L.A. History will be viewable in its entirety once again beginning March 8 as the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County presents Sin Censura: A Mural Remembers L.A. According to the museum, it’s the first time the full-length mural will be shown in a museum setting, “presented across three walls of an intimate gallery to bring visitors eye-level with the 80-foot panoramic work.”

“I am thrilled to see my mural on display at a museum where it will be seen by thousands of school children and visitors curious about our world,” Carrasco said in a press release. “I have many memories of my own visits to the museum in my youth and appreciate the ways NHMLA reaches diverse audiences.”